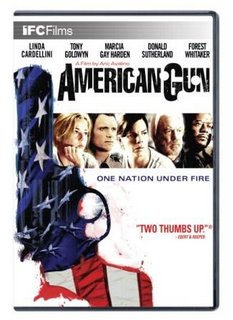

Crash was the big Hollywood salute to the racial divide in America. American Gun is the small independent response to the gun crisis. Both films take a patchwork approach towards identifying the problem, coming at different perspectives from all angles—but whereas Crash needed closure, American Gun accepts the less satisfying but more realistic ending. Aric Avelino is to be respected for this choice; his film comes across at times as gritty as Soderburgh’s Traffic—at other times it seems as obtuse as Gus van Sant’s Elephant. These are both excellent qualities for his film, and the different scenarios allow Avelino to paint a disturbing picture of the real America.

Crash was the big Hollywood salute to the racial divide in America. American Gun is the small independent response to the gun crisis. Both films take a patchwork approach towards identifying the problem, coming at different perspectives from all angles—but whereas Crash needed closure, American Gun accepts the less satisfying but more realistic ending. Aric Avelino is to be respected for this choice; his film comes across at times as gritty as Soderburgh’s Traffic—at other times it seems as obtuse as Gus van Sant’s Elephant. These are both excellent qualities for his film, and the different scenarios allow Avelino to paint a disturbing picture of the real America.There are three central stories, each of which breaks apart into a series of dramatic vignettes. The first, set in Ellisburgh, Oregon, looks at the aftermath of a school shooting at Columbine stand-in, Ridgeline. This is Avelino’s preferred medium: the prelude and coda of violence, and the pressure that an implied threat places on a community. We see, in the opening credits, snippets of the shooters from a video camera: after that, we see an interview with the mother of one of the two shooters, Janet Huttenson, in which she is accused of negligence (to put it politely). As Avelino pulls back, we also meet Janet’s other son, David, who is not exactly the most popular kid in the neighborhood. Much of the drama comes from the tension between mother and son, as both find themselves unable to communicate with the other. We also meet Frank, the first responder on the scene, a tough police officer who is struggling to keep his emotions under control. By the way, all of these events take three years after the initial shooting. It’s just one more reminder of Avelino of how long tragedy can linger and scar a nation.

The second, set in a tough public high school in Chicago, Illinois, looks at the dilemma of a smart student trying to make good without being killed, and also at the cost the principal of such an environment must pay. Led by outstanding performances from both Forest Whitaker and Arlen Escarpeta, these scenes force the conventional teachings of polite society to come to terms with the harsh realities of the unprotected streets. Avelino’s film is not meant to justify or condone gun culture, but these segments do cast an ugly shadow on the blindly adamant anti-gun enthusiasts who probably never worked the late shift at an inner-city gas and liquor store. At the least, American Gun is a conversation starter.

The final city, Charlottesville, Virginia, is the most subtle, but probably of most relevance to the type of person who might view this film. Nothing bad ever happens in White Suburbia, that being the point of White Suburbia, and under Avelino’s eye, nothing bad overtly happens. To the casual viewer, a girl is just thrown against a wall when trying to stop some frat boys from taking advantage of her drugged-out friend. But as the camera remains on her, we can see the crack below the surface, the ugly truth that comes from even the slightest brush with danger. Avelino spends the least amount of time here, but that’s because the implications are clear: we built a world where people need guns to sleep at night.

If some of the individual compartments seem sensationalized, like a confrontation on the front lawn between Janet and her accusatory neighbors, they are balanced by the subtle and often inexplicable moments of grief that penetrate the picture, most of which come from Whitaker’s shaky exterior and lingering gaze. The whole cast is outstanding, and it’s a real surprise that Marcia Gay Harden didn’t walk away with an award for this film.

American Gun isn’t trying to be clever, and it’s not trying to solve the problem. But by illustrating the myriad chambers, if you will, of this loaded gun of a topic, Avelino has put together a sleek and efficient way to deliver this film. Not with a whimper, but with that long foreshadowed bang—one hell of a bullet of a movie.

No comments:

Post a Comment