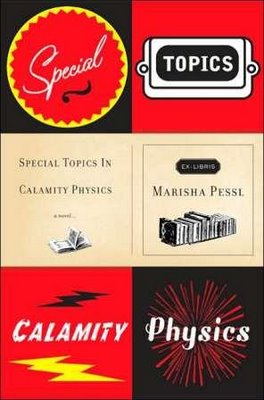

Special Topics in Calamity Physics is a roundabout novel that couples the Marisha Pessl’s (and hence the narrator’s) exquisite knowledge of the literary canon with a coming-of-age murder mystery. Whether or not that’s any good, it is a true or false question that should appear in the Final Exam (Pessl, p. 509). The playful use of citations and the references to popular films is a means of distancing the character from the emotion (L’Avventura meets Gone with the Wind meets Jude the Obscure), but it’s only as enjoyable as the reader wants it to be. Even then, the play on novels (not just words alone) grows routine: too clever by half and then half as clever as it was. Strive as it might for epic qualities, the plot itself never rises above that of a smarter-than-your-average-noir, and Pessl’s characters come across as either too mysterious or as an intellectual gloss of a real person.

Special Topics in Calamity Physics is a roundabout novel that couples the Marisha Pessl’s (and hence the narrator’s) exquisite knowledge of the literary canon with a coming-of-age murder mystery. Whether or not that’s any good, it is a true or false question that should appear in the Final Exam (Pessl, p. 509). The playful use of citations and the references to popular films is a means of distancing the character from the emotion (L’Avventura meets Gone with the Wind meets Jude the Obscure), but it’s only as enjoyable as the reader wants it to be. Even then, the play on novels (not just words alone) grows routine: too clever by half and then half as clever as it was. Strive as it might for epic qualities, the plot itself never rises above that of a smarter-than-your-average-noir, and Pessl’s characters come across as either too mysterious or as an intellectual gloss of a real person. There’s nothing wrong with Pessl’s technique: her story begins with a perfunctory hook, (one year after Blue van Meer’s finds her overly friendly teacher, Hannah Schneider, dead) and then galvanizes the audience with its rapid introduction to Blue’s Tragic Past and her educational but distant relationship with her father, Gareth. The pace doesn’t slow, though the passage of time does, and up through the first half of the book, it’s a dazzling smorgasbord of showboat smarts, a soupcon of stories. By the second half, the mystery is no longer as captivating, and its resolution—purposely frustrating—is, naturally, frustrating.

Now, I’m not against the use of so many sources—it gives the clever literary archeologist many a bone to find when reading between the lines—but does the canon need to be presented as if it were a canonball [sic]? The goal of fiction is, undoubtedly, to reveal as many inner truths as non-fiction, and is thus entitled to its clever appropriations:

“I wanted to take a fire poker to his too, too solid flesh (anything hard and pointy would do) so his hard-bitten face would deform in fear and out of his mouth, not that perfect piano sonata of words, but a strangled soul-ripped Ahhhhhhhhhh!, the kind of sob one hears reverberating through damp chronicles of medieval torture and the Old Testament. Hot tears had begun their exodus, making their slow, stupid way down my face.” But for all that run-on, not to mention the Shakespearean and Biblical styling, where’s the heart?

Pessl’s novel actually conveys the majority of its wisdom through the bonhomous lectures of her Father Figure, a man whose maxims populate the pages with originality and style. When the story segues into a violent scene, Blue quotes her father:

“All worthwhile tales possess some element of violence...Simply reflect for a moment on the utter horror of having something threatening lurking outside your front door, hearing it huff and puff and then, cruelly, callously, blowing your house down. It’s as horrifying as any story on CNN. And yet where would the ‘Three Little Pigs’ be without such brutality? No one would have heard of them, for happiness and placidity are not worth recounting by the fire, nor, for that matter, reporting by a news anchor wearing pancake makeup and more shimmer on her eyelids than a peacock feather.”This is such an energized, rhapsodic character, that though he stands at the periphery of a story that mainly focuses on Blue’s relationship with a pack of kids known as the “Bluebloods” and their teacher, Hannah, he is the one who dominates the novel.

Ultimately, Pessl falls prey to a desire to be the next Nabokov, and while Special Topics in Calamity Physics may be an original presentation, if its glitter is all gold, some of it’s just pyrite. It’s also not that original—Pessl may be the only author to use the names of other novels as her chapters, and she may call her table of contents the “Required Reading,” but none of this actually ties into the story; at least not in any significant way. Jonathan Safran Foer’s delightfully loopy chapter headings and narrative tone fit the scope of his work in Everything is Illuminated, and if you’re looking for a young intellectual’s attempt to grasp the world around him, David Mitchell’s proven to be the go-to writer for bountiful prose, and Black Swan Green isn’t too far off from Calamity Physics.

If you’re a reader who favors inelegantly used elegance or an abundance of the mundane, Calamity Physics is a smart, wicked beach read. But if you’re looking for deep literature; something that goes beyond the surface of the text, you might want to read elsewhere, or just crib the answers to her Final Exam off someone else—there’s no need to read 500 pages for such an untidy ending.

No comments:

Post a Comment